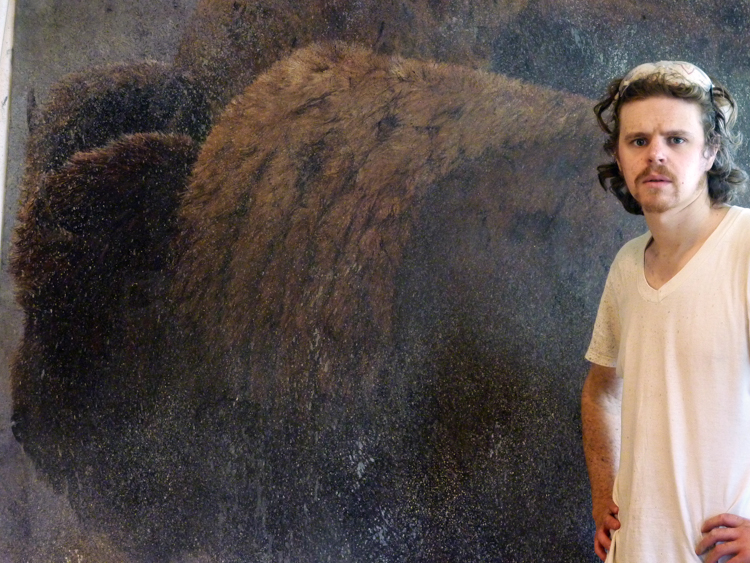

Detail from “Sky Blue”

Artwork

I long ago came to the conclusion that even if I could put down accurately the thing that I saw and enjoyed, it would not give the observer the kind of feeling it gave me. I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at—not copy it.

—Georgia O’Keeffe, from her book Georgia O’Keeffe

I want my paintings to be paintings in the most straightforward and physical sense: objects: canvases covered in pigment and oil: brushed on, smeared on, spattered on, slapped on, scraped with a knife. The materials should be prominent, the techniques evident, and they should work together palpably, should attract and hold the attention of the viewer, visually foremost, but also imaginatively, inquisitively, and emotionally. To me at least, this performance of the physical object in the mind of the viewer is the only real abstraction in art.

To varying degrees, I use my paintings to demonstrate that philosophy: since the conveyance of an image in a painting is really an artifice, I want to show that: by covering up the image of a bison with splashes of color or duplicating it like a giant painted stamp or breaking its organic features with geometric textures. I have no interest in paintings that seem to precisely replicate life in the manner of a photograph. Photography performs that function perfectly adequately. A painting is a painting.

I have used bison as my subject matter since I was a boy. I have been interested in portraiture and illustration and absurdist scenes and other animals as well, of course, but I always seem to come back to bison and now have committed my focus to them: they are such iconic, monolithic beasts: from a far, enormous, still boulders; up close, masses of muscle, horn, and hide very much alive; even a sleeping buffalo cannot help but be full of a violent energy. To the best I am able, I want my paintings to convey that energy, that feeling of being in the presence of these animals. That is why I paint to scale and apply the paint thick.

Detail from “Butting Heads”

Detail from “Butting Heads”

Background

When I was six, my father took me to Nez Perce Ford to fish for cutthroat trout on the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park. It was called Buffalo Ford back then, and though I can’t remember how good the fishing was that day, I do recall standing next to my father, watching a bull bison cross downstream. The crossing in itself was nothing remarkable. We often camped in Yellowstone and were used to seeing bison, sometimes many bison, sometimes far too close, only feet from our car.

But this was a good sized bull, and he moved with a sort of orneriness that impressed me. After reaching our side of the river, he circled up on top of the hill behind us in the trees where our Ford Escort was parked. We couldn’t see him. A game trail came down from the top of the hill, leading to the bank where we were. A fallen log crossed the trail at the bottom. No one else was fishing that day, at least that I can remember. For a while, we fished and didn’t think much about the buff, though I was curious about how we’d approach our car if he was still up near it.

Then we heard him grunt. A bison’s grunt is distinct and loud and sounds a bit like a lion’s growl. We turned and there he was: no more than twenty yards away, up at the top of the hill, perched on the game trail, staring down at us. He took a step forward then broke into a gallop, which was breathtaking in a terrifying kind of way. As he charged, my father put a hand on my shoulder and pushed me in back of him, which I would guess was more instinctual than practical. A bison bull can weigh over 2,000 pounds. But we were lucky. At the bottom of the hill, he stumbled going over the fallen log, changed course, ran past, and kept going. At his closest, he was fewer than ten feet from us. I have never forgotten that day.

About bison

American bison once numbered in the tens of millions. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, they had been shot nearly to extinction by white settlers, hunters, and soldiers, with the number of wild animals dropping to an estimated low of just 85 individuals. The U.S. Government promoted this slaughter as a means of depriving Plains Indians of one their most important resources, a chapter in what was essentially the continuing tragedy of the genocide of Native Americans.

Today, around 15,000 wild bison live on public lands, with approximately a third of that number in Yellowstone National Park. Increasing their population and range is vital for the sustainability of plains ecosystems where certain farming and ranching practices have depleted the nutrients in the land, creating conditions similar to that of the Dust Bowl. To learn more about bison reintroduction, visit the American Prairie Reserve website.

About the artist

About the artist

Thomas grew up in Bozeman, Montana. As a boy, he studied watercolor painting with Susan Blackwood and later oil painting with Howard Friedland. He also studied with Mark Sullivan.

During college, he spent a semester in Rome with the Tyler School of Arts, studying painting and drawing with Stanley Whitney and Marina Adams and printmaking with Mario Teleri Biason.

He now lives with his wife and child in Seattle, Washington.